In our newest blog series So you want to be a…?, we explore the different positions found on film and television productions – from production assistants to producers and everything in between! We’ll chat with industry professionals who have made a successful career in their field to learn how they got to where they are and how others can find a similar path.

For the first blog in the series, we interviewed none other than our very own film commissioner, Bruce Harvey. A lawyer-turned-producer, Bruce produced for 25 years in Calgary before returning to his hometown of Ottawa in 2014 to accept the role of film commissioner.

Ottawa film commissioner and former producer Bruce Harvey

First off, can you tell us what a producer does?

It’s probably the broadest category of any in film and TV. Producers choose projects, work with writers to develop the screenplay, raise financing, hire key crew, troubleshoot issues that arise during production, support the director in achieving her or his vision for the project, arrange for distribution, oversee the final editing and post-production…or none of those things. In some cases, the producing credit may just go to a friend or family member of a powerful actor or director.

Did you always want to be a producer? How did you get started?

I did not always want to be a producer. I originally wanted to be a computer scientist, then a lawyer. After practicing law for seven years, I had a mid-life crisis and left the law firm. A past client and friend of mine in Calgary asked me to help produce his film. Since I had been an entertainment lawyer and knew that side of the business, I was able to provide valuable assistance to the production of the film and obtain an incredible amount of on-the-job training for myself. When the senior partner in my old law firm told me I’d have to be crazy to produce films, my fate was sealed.

What skills or training does a producer need to be successful?

The easiest way to be successful as a producer is to be very rich, since then you can finance any film you want and give yourself the credit, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll make your money back. If you’re not rich, it helps to have a great understanding of the entire production team since you are essentially the head of that team. Locations, accounting, assistant directors, production management – you’re responsible for all those.

You should also understand story structure so that you can be a useful partner to the director, writer, cinematographer, and designer in production and the editor and their team in post-production. If you don’t know all the tasks required to be a producer, you can always hire someone to do those for you, like a lawyer, accountant, executive producer or producer’s rep, but the costs of these services are going to be substantially higher than the financing available to producers on low budget films. The more you learn yourself about tax credit legislation and guidelines, the more you’ll be financially successful. You also need to have a great understanding of how union contracts work in your jurisdiction, have a good go-to production manager, and establish valuable relationships with department heads so that during the development and prep stages, you get a realistic idea of the costs. Finally, I always say that script breakdown, scheduling, and budgeting are skills that every producer must know – or make sure you have the money to pay someone to know it for you.

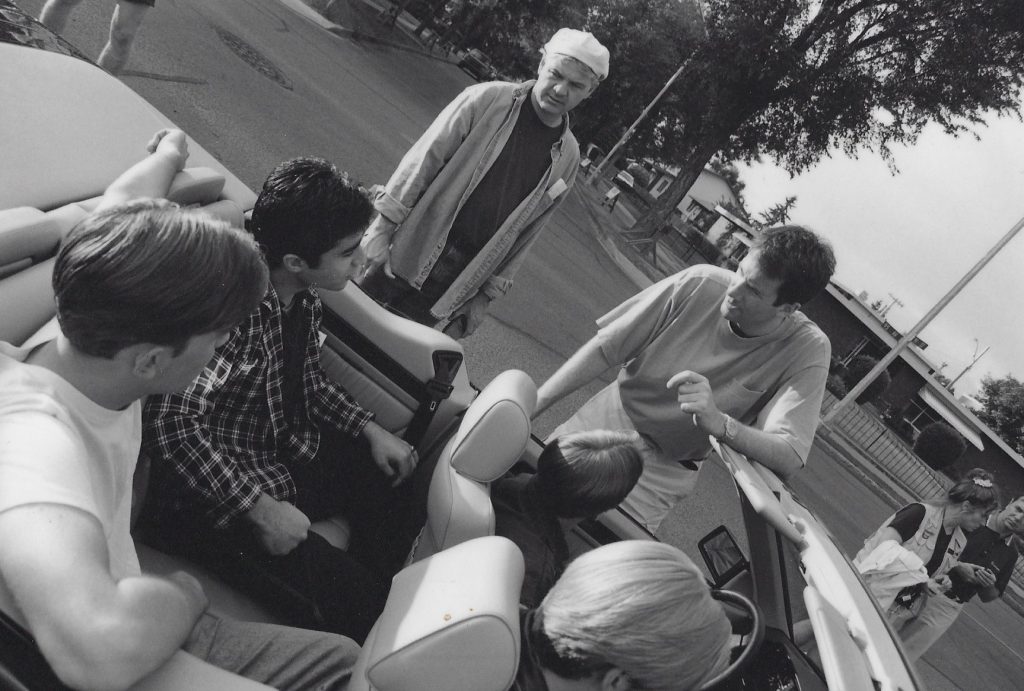

Bruce (top left) with director Rick Stevenson on the set of the TV movie “Question of Privilege”

Is there anything you wish you knew before becoming a producer?

I wish I knew more about story structure. Learning about scheduling, breakdowns, and budgeting came fairly easy to me, and I already knew the legal and accounting sides of production, but understanding story structure and being an effective partner to the writer and director would have improved my earlier films. Also knowing that Emotion trumps Plot 2 to 1 is something I wished I’d learned earlier; it’s a key to Walter Murch’s Rule of Six in editing and it was cherished advice I received from the great and humble Canadian director Arthur Hiller. To be honest, there are a million things I wish I’d known, these are just the two biggest.

Do you have a memorable experience as a producer that you can share?

I have tons! As a producer, your main role when production starts is dealing with problems, and those always come up. I always try to work on set when a project of mine is shooting, but on one particular shoot, I had to go into the office for a couple of days to deal with an urgent financing issue that came up. Later that day, I got a call from the 1st AD saying the lead actress was in her trailer, she was saying that she was unable to go to set and that she needed to talk to me. I rushed back to set and found out that the actress was concerned that I didn’t like her performance (since I hadn’t been on set for a few hours) and she was feeling like she wasn’t in the right mindset to perform that day. That’s when I realized that no matter how big your issues are, other issues are just as important – you need to focus on all the issues, not just the biggest ones, to keep the machine moving. I told the actress that she was doing a great job, how all the cast and crew thought she was doing marvellously, and I tried to get her excited to go back to work, which she eventually did. It’s hard to be an actor, to have up to 100 people or more staring at you while you do your job. It’s important for the key creatives to create a supportive environment where actors can fully express their talent.

Bruce on the set of the TV movie “Silent Cradle”

What advice would you give aspiring producers in Ottawa?

Read. Read every moment you get. Whenever you go to a foreign city that has a good film program (like UCLA or USC in Los Angeles), read the required texts for those programs. Read anything you can by Walter Murch for editing; for writing, Save the Cat is a great resource that I often recommend. You should also read as much as you can about budgeting, breakdowns, and scheduling. All those are critical – understanding tax credits for a producer is like being able to add numbers if you’re an accountant. Attend as many seminars as you can where you can learn and ask questions from professionals who would normally charge you hundreds of dollars to work on your film individually. It’s better to spend $1,000 on a seminar than spend $50,000 on a consultant.

I would also say to think about who your audience is; it’s not the people at home watching your film or TV project, it’s the financers, distributers, and broadcasters that are funding and disseminating your product. If you have an incredible romantic comedy, you shouldn’t be going to horror distributors or sports broadcasters – you need to identify which buyer distributes that type of film. It doesn’t matter who the end audience is, your target is always the distributor or broadcaster. No matter how great the project is or could be, they’re not going to do it if it’s not what they do. And remember, just because someone says no, it doesn’t mean the product isn’t good, it just means it’s not good for them – you may just have been knocking on the wrong door.

People always say if it was easy, everyone would do it, and that’s so true when it comes to producing, but it’s actually really hard work. When you’re faced with immovable obstructions for getting your film done, that’s when you earn your money. The greatest moments in my career were when people told me something was impossible, then I could really show my skillset.